Since the earliest days of cinema, westerns have been one of Hollywood’s favorite genres. 1908’s “The Great Train Robbery” was one of the most successful early films, while 1939’s “Stagecoach” kicked off a golden age of westerns that lasted until the mid-20th century, making stars out of actors like Gary Cooper, James Stewart, Robert Mitchum, Henry Fonda, Glenn Ford, and Walter Brennan.

While thought of as a hallmark of American movies, international westerns grew in popularity, too. European films referred to as “Spaghetti Westerns” emerged in the ’60s thanks to Sergio Leone’s “The Man With No Name” trilogy, while experimental filmmakers like Alejandro Jodorowsky coined the term “acid western.” Westerns often meld with other genres as well. Films like “Blazing Saddles” poke fun at western clichés, while science fiction borrows heavily from westerns; famous sci-fi properties like Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, “Star Wars,” and “Firefly” reimagine western storylines in an intergalactic setting, while movies like “Westworld” and “Back to the Future: Part III” directly combine the genres.

Given the expansive history of the genre, narrowing down the greatest westerns of all-time is no easy task. These 20 films epitomize everything the western is capable of: grand adventures, romances, comedies, historical tales, and even social commentaries.

Once Upon A Time In The West

Sergio Leone kickstarted the “Spaghetti Western” subgenre with his trilogy of films starring Clint Eastwood, but one of his greatest films featured an entirely different cast of characters. “Once Upon A Time In The West” is a meditation on the western genre, exploring the last days of the American frontier as the construction of a transcontinental railroad threatens to put cowboys out of work. Characterized by Leone’s slow pace and attention to detail, it’s a melancholy reflection on the passing of an era.

Despite the thoughtful commentary, “Once Upon A Time In The West” has a gripping adventure story at its center. A nearly wordless gunslinger simply known as “Harmonica” (Charles Bronsan) debuts in one of the coolest character introductions of all-time, in which he slays a group of assassins who threaten local ranchers. Harmonica’s backstory is unveiled when he comes to the aid of the widow Jill McBain (Claudia Cardinale), who tries to keep her husband’s business alive.

McBain enlists Harmonica to end the threat of bounty hunter Frank (Henry Fonda), who uses the dying economy to excuse violent actions. Fonda is cast against type, and the likable Old Hollywood star transforms into a remorseless criminal willing to kill children. “Once Upon A Time In The West” continues to be influential, as filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan, and “Breaking Bad” creator Vince Gilligan have cited it as a favorite.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

The last western film from John Wayne and John Ford is a surprisingly downbeat commentary on the perils of hero worship. Told entirely in flashback, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” has a chilling final line that questions why violence is perpetual on the frontier. Although color film was already mainstream when the film was released in 1962, Ford shot the film in black and white, giving it the pensive feeling of a fleeting memory of a bygone era.

“The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” follows respected politician Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) as he travels to the funeral of the rancher Tom Doniphon (John Wayne). It’s initially unclear why an important political figure cares so deeply about the life of a working class man, but the film delves into their early friendship, showing how Stoddard helped establish a new political framework for Doniphon’s hometown, Shinbone. The town resists political meetings and debates about statehood, but an empathetic Stoddard simply wants to save Shinbone from isolation. Doniphon distrusts Washington, but respects Stoddard.

Their advancements are threatened by the vicious bounty hunter Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin), who aims to take over the town before it is fully incorporated within the U.S. Government. Stoddard is forced to take up a weapon and engage in conflict for the first time, while Doniphon struggles to keep the peace. Both men are out of their comfort zones, forced to face the limits of their abilities.

Unforgiven

After working with Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood became one of the most popular western stars of all time, and leveraged his fame into a successful directing career. Twenty years after his directorial debut, “Play Misty For Me,” Eastwood released his masterpiece, “Unforgiven.” One of the darkest westerns ever made, “Unforgiven” was Eastwood’s last western, and focused on characters forced to reckon with their past actions.

Eastwood’s character, Will Munny, is not a hero. A former bounty hunter now living in isolation with his two children. Munny is called back into action when an up-and-coming gunslinger called the Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett) asks for his help tracking down two cowboys that scarred a local woman. Reteaming with his old ally Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman), Munny comes face-to-face with the corrupt sheriff Little Bill (Gene Hackman). Bill’s brutality towards local residents prompts Munny to return to a life of crime he thought was behind him.

“Unforgiven” suggests that violence is cyclical, and that those drawn to it are doomed to repeat their failings. Munny can’t escape his past, and the other characters face the consequences of employing him. The final confrontation, in which Munny battles Bill’s men, is grizzly, with subtle acting from Eastwood. Although his tough-guy persona is well utilized in more crowd-pleasing westerns, Eastwood delivers threats without a hint of irony. With all of the baggage Eastwood brings to the screen, you can’t help but believe him.

The Searchers

Hailed by “Sight and Sound” as one of the ten greatest films ever made, “The Searchers” is both a beautiful and haunting western. Gorgeously capturing the scope of the west through portrait-like cinematography, John Ford showed his affinity for natural beauty. George Lucas cited the visual poetry of “The Searchers” as a major influence on “Star Wars,” and pays homage to the film when Luke discovers the destruction of the Lars Homestead in “A New Hope.” The film’s frank depiction of the genocide of Native Americans does not romanticize history, and John Wayne’s psychopathic character is a distinct departure from the heroic roles he’s known for.

Civil War veteran Ethan Edwards (Wayne) looks to retire to his family home with his brother Aaron (Walter Coy). However, the homestead is suddenly attacked, and while both Aaron and his wife, Martha (Dorothy Jordan), perish, Ethan suspects that his eight-year-old niece Debbie (Lana Wood) has been abducted by Comanche. Ethan’s adopted nephew, Martin (Jeffrey Hunter), helps him lead a search party, but the grizzled former Confederate uses the quest to fuel his bloodlust and bigotry. Martin’s mixed race heritage creates additional tension between the two.

The searing incitement of cyclical violence in “The Searchers” is explicit, as Ethan is enraged when he learns that an older Debbie (Natalie Wood) has joined a Comanche tribe. “The Searchers” has ambiguous themes that invite analysis; given Ethan’s attachment to Debbie, who he bestows his medals to, it’s possible that she is in fact his daughter through infidelity.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Sergio Leone first introduced the Man with No Name (Clint Eastwood) in “A Fistful of Dollars,” where he comes to the assistance of a border town when rival families threaten its citizens. The mysterious bounty hunter returns in “For A Few Dollars More,” chasing down bandits who escaped imprisonment. The enigmatic character gradually revealed his heroism, and the trilogy’s final installment “The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly” sees him embark on an epic quest for gold during the final days of the Civil War.

Now referred to as “Blondie,” the Man forms an unlikely partnership with the fast-talking thief Tuco (Eli Wallach) as they compete in a treasure hunt against the sadistic mercenary Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef). The three men duel in an epic final gunfight, which has been homaged and parodied countless times since. Leone also incorporates subtle commentary about the destructive nature of war as the characters travel through devastated battle camps.

At nearly three hours long, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly” is entertaining throughout thanks to the stylized action sequences, the comedic banter between Blondie and Tuco, and the iconic score by Ennio Morricone. Each installment in the trilogy stands alone, but “The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly” is a great sendoff for its hero.

High Noon

“High Noon” was a novelty in 1952, featuring a more conflicted hero than the fearless gunslingers of earlier westerns. It presents a complex moral dilemma and focuses on intimate conversations over non-stop action, and its pacifist message generated controversy. The recurring appearance of a ticking clock adds tension to the story, making its 85 minutes fly by.

Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper) is on the eve of retirement, preparing to leave his duty to focus on raising a family with his new bride, Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly). He receives word that the dangerous murderer Frank Miller (Ian McDonald), whom Kane had imprisoned earlier in his career, is set to be released from prison and will arrive by train to threaten the town once more. Amy informs her husband that she will depart on the noon train with or without him, and Kane must weigh his conflicting loyalties as Miller gathers a band of criminals.

The film’s final sequence, in which Kane casts his badge aside after dueling Miller, is a defining moment in western cinema; in this moment, Kane gains the love of the townspeople who feared he’d leave. Cooper won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his sensitive, yet commanding performance. The film was also awarded Best Editing for its meticulous pacing, and earned both Best Original Score and Best Original Song for its memorable music.

The Magnificent Seven

Akira Kurosowa’s 1954 classic “Seven Samurai” told the story of seven very different warriors who reluctantly join forces in order to protect a poor town threatened by a gang of murderers. It’s a timeless tale about brave heroes who defeat evil against seemingly insurmountable odds. In 1960, director John Sturges reimagined the story as an American western adventure. “The Magnificent Seven” is a creative remake that retains the themes of “Seven Samurai” even while moving the action to a different setting.

Seven distinguished lawmen join forces when a raider named Calvera (Eli Wallach) assaults a Mexican village. The honorable Chris (Yul Brennar), enigmatic traveler Vin (Steve McQueen), impulsive hustler Chico (Horst Buchholz), troubled career man Bernardo (Charles Bronsan), war veteran Lee (Robert Vaughn), fortune teller Harry (Brad Dexter), and weapons expert Britt (James Coburn) have little reason to trust each other, but are united in their noble cause. The cast has terrific chemistry as they compare their different experiences and work together to teach the villagers how to protect themselves.

While the brilliant “Seven Samurai” score from composer Fumio Hayasaka is tough to emulate, the energetic main theme of “The Magnificent Seven” by the great Elmer Bernstein is instantly recognizable. While a remake itself, “The Magnificent Seven” was remade again in 2016 from Antonie Fuqua and Denzel Washington — the new film contains fun callbacks for those that love the original.

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford

Although few modern westerns are as worthy as those from the golden era, this 2007 masterpiece from director Andrew Dominick is an exception. “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford” is a fascinating deconstruction of the lionization of western outlaws told through the eyes of an obsessive fan. It’s an astute commentary on western mythology, placed in a grittier setting.

Robert Ford (Casey Affleck) has grown up idolizing the famed train robber Jesse James (Brad Pitt) and wants nothing more than to join his band of criminals. James’ crew, including Ford’s brother Charley (Sam Rockwell) and James’ cousin Wood Hite (Jeremy Renner), mock the starstruck younger man, but he eventually gains an audience with James, who recruits him for a series of heists. Ford’s loyalties stray as he becomes disillusioned by his hero’s cruelty and betrays him. Pitt weaponizes his charisma to give depth to a reprehensible character, and Affleck is perfect as a timid, yet jealous adolescent.

The cinematography by Roger Deakins is among the most beautiful to ever grace the screen, and incorporates still images and photos to authentically recreate life in the 19th century. Dominik’s film had a challenging road to release, was edited several times by Warner Brothers, and underperformed financially. However, the introspective themes and gradual pacing make “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford” a modern classic worthy of renewed acclaim.

Rio Bravo

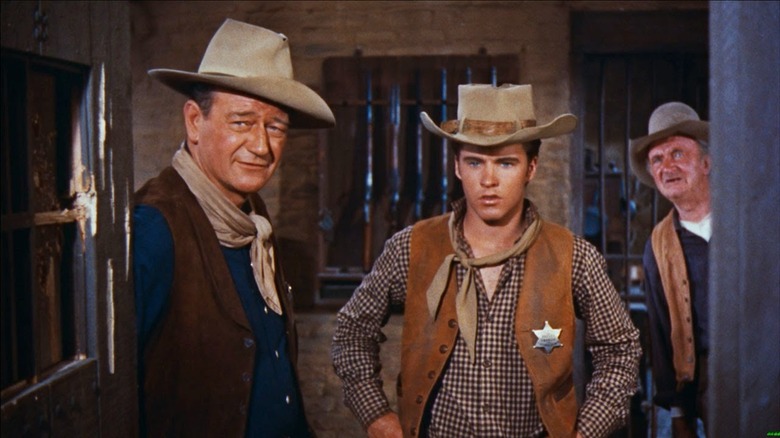

Thanks to the sharp dialogue between its central characters, “Rio Bravo” is one of the most entertaining classic westerns. It’s no surprise that it’s a favorite of Quentin Tarantino, who stated that it’s one of his favorite films of all-time, and notes that he was inspired by its “hang-out” approach when writing “Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood.” The crackling mix of comic banter and exciting gunfights make “Rio Bravo” an early action-comedy.

Sheriff John Chance (John Wayne) enlists the help of town drunk Dude (Dean Martin), former lawman Stumpy (Walter Brennan), and rising street fighter Colorado (Ricky Nelson) to keep the dangerous outlaw Nathan Burdette (John Russell) in prison while his loyal private army plots to free him. The heroes are forced to stay in close quarters as they protect the prison outpost while awaiting the arrival of the U.S. Government militia forces. Wayne adds gravity to the role, but finds room for humor as Chance grows annoyed by his bickering allies.

The plot is similar to “High Noon,” but the two films were in competition with each other. Hawks disliked the idea that a sheriff would consider abandoning his duty, and created the unflinching heroes of “Rio Bravo” as a response. Despite their different approaches, both films are classics in their own right.

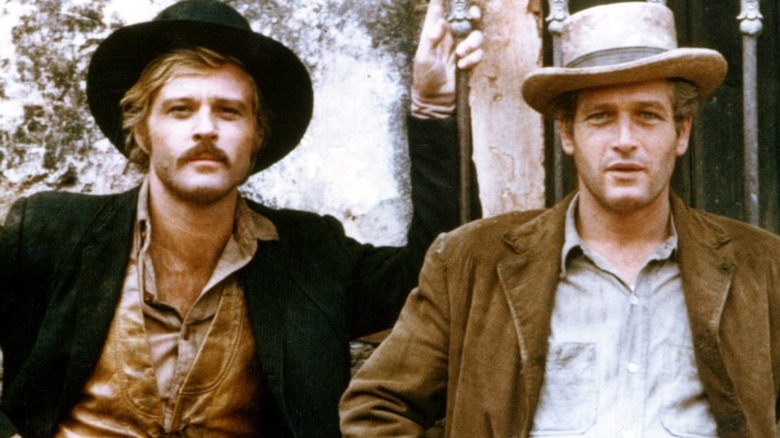

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Paul Newman and Robert Redford would go on to star in the Best Picture-winning heist film “The Sting” together, but their earlier team-up, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” is the better movie. Featuring exciting train robbery setpieces and a quirky use of music (including an iconic sequence set to “Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head”), it’s a breathlessly entertaining thrill ride from start to finish. Despite the comedic elements, the film does hint at the darker side of the criminal lifestyle through its ambiguous ending.

Newman and Redford star as the titular leads, two lifelong bank robbers who lead the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. Although Butch is more experienced, both are extremely confident, and Newman and Redford do a great job capturing the clashing of personalities while still making it clear that the characters care for one another. Their banter breathes life into crackling dialogue from legendary screenwriter William Goldman.

“Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” reflects on why adventure-seeking outlaws are continuously drawn back to their dangerous lifestyles. Even with enough winnings to sustain themselves, and presented with the option for a normal life, Butch and Sundance continue to keep doing what they know best.

McCabe & Mrs. Miller

Writer-director Robert Altman described his revisionist period film “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” as an “anti-western.” Despite being set in the growing American frontier during the early 20th Century, it’s far from an exciting adventure, taking a much more realistic approach to its historical setting. Altman’s crew built an entire town from the ground up, and the cast and crew lived on the set throughout filming. Not only did this commitment to authenticity help recapture specific historical details, but seeing the visible discomfort of the actors in the isolated environment makes the movie’s dreary tone more effective.

John McCabe (Warren Beatty) is a scheming gambler who hides out in a secluded Washington community. Sensing a potential profit opportunity, McCabe deceives the local residents into helping him establish a brothel to attract out-of-towners. McCabe boasts that he’s a gunfighter, but in actuality flees at the sight of danger. His brothel attracts the mistress Constance Miller (Julie Christie), who improves his hastily constructed operation and begins to fall for him. Outlaws seeking revenge on McCabe arrive in town and threaten their relationship.

The film finds beauty when observing nature and contrasts it with the ugliness of McCabe’s character and his false promises to the workers. Beatty delivers a sensitive performance, and it’s understandable why his deceptive nature effectively captures the town’s attention. The terrific original songs by Leonard Cohen make the film even more somber.

Stagecoach

“Stagecoach” is one of the most important westerns of all-time, setting many precedents for the genre, including an admiration for natural environments and a cast made up of morally ambiguous characters. It was also notable as John Wayne’s breakout role; Wayne’s introductory scene as the brave everyman known as “The Ringo Kid” is one of the greatest screen debuts of all time.

“Stagecoach” follows a group of strangers as they travel by coach from Arizona to New York. They are forced to work together in order to survive the attacks of Apache raiding parties. It’s a movie full of interesting social commentary; although the characters have different professions and belong to various social classes, they’re all equal when their lives are in danger.

The film creates tension by confining the characters to the coach, and is still entertaining today. However, certain elements have not aged well; the Apache characters are treated purely as villains and do not have any depth. On a more positive note, the prostitute Dallas (Claire Trevor) has an agency that was rare among female characters in early westerns.

Red River

Although westerns are commonly thought of as pure entertainment with obvious good guys and bad guys, the Howard Hawks classic “Red River” is a dramatic character study without clear cut heroes and villains. The film follows ranchers Thomas Dunson (John Wayne), Nadine Groot (Walter Brennan), and Dunson’s adopted son Cliff (Montgomery Clift) as they embark on the first cattle drive from Texas to Kansas. While the time passes gradually, “Red River” steadily ramps up tension as the former allies turn on each other. Dunson, overcome by greed, considers stealing the business for himself.

Wayne is terrific in a role that requires him to slowly become unlikeable; Hawks brings out a vulnerable side to Wayne that wasn’t seen in Ford’s more masculine films. As a tortured son forced to reckon with his father’s choices, Cliff is incredibly sympathetic. Although inspired by history and the real-life feuds among early settlers, the story goes in surprising places, especially once the cattle drive attracts the attention of war parties.

Shane

“Shane” is a mature depiction of the last days of the American West, when a more connected nation didn’t require frontier justice from independent gunslingers. However, one farm still needs a drifting gunfighter (Alan Ladd) to stand up against the ruthless cattle baron Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer). Shane is reluctant to settle in this secluded community, but can’t ignore his desire to protect the innocent, and bonds with the young boy Joey Starrett (Brandon deWilde), who idolizes him.

“Shane” popularized the idea of a former hero returning to duty after retiring. Ladd gives a heartbreaking performance as Shane considers his destiny, and his relationship with Joey is remarkably poignant. “Shane” was incredibly influential on other films, especially the X-Men spin-off “Logan.” “Logan” also features an older hero reminiscing on his life, and James Mangold included several clips from “Shane” in his film, making the parallels explicit.

Dead Man

It’s exciting when bold filmmakers revitalize the western by fusing it with other genres, and Jim Jarmusch created a distinctly odd absurdist comedy with the 1995 western “Dead Man.” While “Dead Man” replicates elements from older films through black-and-white cinematography and meticulous production design, “Dead Man” also includes elements of fantasy, raunchy comedy, and shocking violence that are wholly unique. It’s an unpredictable story, and one of Jarmusch’s best films.

“Dead Man” follows the cowardly accountant William Blake (Johnny Depp) as he travels to a frontier town in order to take a job he’s been promised. Upon arriving, Blake realizes that he’s no longer up for the job and is forced to flee when he becomes the target of the ruthless bounty hunter Cole Wilson (Lance Henrikson).

Blake receives mysterious visions throughout the film that guide him, adding a spiritual element to “Dead Man.” An untraditional score by Neil Young also adds a sense of uneasiness, and the bizarre dialogue adds intentionally awkward comic relief.

The Shootist

John Wayne’s final film was in this touching tribute to his own career. While filming, Wayne was suffering from health issues; similarly, his character, J.B. Books, is an older gunslinger recovering from a gunshot wound he’d suffered a decade earlier. The parallels make the film particularly emotional, as Wayne discusses his deteriorating condition with his doctor, Dr. E. W. Hostetler (James Stewart). Seeing Wayne and Stewart reunited is a fun reference to their older collaborations.

While the meditative approach that “The Shootist” takes can be grueling, the film is heartwarming, too. Books falls in love with housekeeper Bond Rogers (Lauren Bacall) and takes her son Gillom (Ron Howard) under his wing. As Gillom grows aware of Books’ legacy and seeks to become a hero of his caliber, Howard injects the film with some much-needed humor. However, Books warns Gillom about the dangers of his profession, and reveals the toll that killing has taken on him. Wayne’s final act of onscreen heroism during the film’s climactic shootout puts a perfect cap on his career.

Destry Rides Again

James Stewart would become known for his gritty, serious performances in western films, but he explored more westerns’ more playful side early in his career. 1939’s “Destry Rides Again” is a heartwarming and hilarious romp. Stewart was one of classic Hollywood’s most charming stars, and “Destry Rides Again” sees him play a sincerely noble character distinguished by his dedication to nonviolence.

Tom Destry (Stewart) arrives in Bottleneck and is tasked with bringing order to the violent town, but refuses to carry a gun. The villagers mock his pacifism, but he proves his merit after beating a group of thugs in a sharpshooting contest. Destry suspects that the town’s previous sheriff, Keogh (Joe King), has been murdered, and teams up with the saloon singer Frenchy (Marlene Deitrich) to unravel the mystery. Frenchy is initially skeptical that Destry’s passive approach will be effective, but grows to respect the new sheriff’s earnestness and begins to fall in love with him.

“Destry Rides Again” features great original songs, including “See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have” and “You’ve Got That Look,” which contribute to the lighthearted tone. The family-friendly approach makes “Destry Rides Again” a great film to introduce younger audiences to westerns.

One-Eyed Jacks

“One-Eyed Jacks” survived a troubled production to become a western classic. Originally, Stanley Kubrick was going to direct the technicolor western, but dropped out two weeks before filming after disputing the budget with Paramount Pictures. The film’s star, Marlon Brando, stepped in and directed a five-hour version with a nihilistic finale, but Paramount grew concerned, forcing Brando to cut the runtime in half and change the ending. Unfortunately, much of the footage was destroyed and Brando’s director’s cut will never see the light of day. The experience was so challenging that Brando never directed another film.

However, the version of “One-Eyed Jacks” that was released is still a terrific western. Brando stars as a bank robber nicknamed Rio “The Kid” who is betrayed by his mentor “Dad” Longworth (Karl Madden) and spends five years in prison. After Rio is released, Dad denies his version of events and boasts that his former partner will never defeat him in a duel. Rio reluctantly pursues his old friend, despite once loving him.

Brando makes the emotional core of the movie feel authentic, as he had a personal connection to the story: Brando had a troubled relationship with his father, and used the relationship between “The Kid” and “Dad” to reflect on his own experiences.

Django

Spaghetti westerns don’t get much more ridiculous than “Django.” The controversial thriller was accused of being one of the most violent films ever made on its release in 1966 and was banned in several territories. And yet, it also made director Sergio Corbucci one of the most prominent spaghetti western filmmakers, thanks to his inclusion of dark comedy and savage anti-hero characters.

Django (Franco Nero) disguises himself as a war veteran and dispatches a gang of vicious outlaws loyal to crime lord Major Jackson (Eduardo Fajardo) alongside a border town. After saving a defenseless woman Maria (Loredana Nusciak), Django discovers that the town is a neutral zone between Jackson’s Red Shirts gang and a company of revolutionaries sworn to General Hugo Rodríguez (José Bódalo). Django reluctantly stays to protect the villagers from the gang war.

One of the quintessential spaghetti westerns, “Django” remains a cult classic. Quentin Tarantino loved the film so much that he brought back Nero for a cameo appearance in “Django Unchained.”

Winchester ’73

The first western made by director Anthony Mann and James Stewart utilizes a creative structure to explore cyclical violence on the American frontier. The film changes its point-of-view character as the titular Winchester 1873 rifle passes between owners, while a detective named Lin McAdam (Stewart) traces the history of the weapon, following its story as different criminals claim the gun as their own

McAdam is a darker protagonist for Stewart, and is known for his proficient gunmanship. Despite his arrogance, McAdam is honorable, traveling between towns to train villagers how to protect themselves. The nonlinear narrative makes the central mystery more engaging, and McAdam is forced to start his search over whenever a new owner takes possession of the gun.

McAdam is one of Stewart’s most memorable characters, but cinephiles may be surprised to see Tony Curtis and Rock Hudson appear in “Winchester ’73” too, making small cameos before they became household names.

BY LIAM GAUGHAN