The Wild, Wild West would not be the, well, Wild West that we know today without the O.K. Corral and the famous gunfight that erupted there on a late October afternoon in 1881.

The romanticized version of the American cowboy, tin stars, quick draw gunfights, saloons on dusty streets, and unending desert landscapes wouldn’t hold such a firm place in our consciousness if not for this infamous showdown. The one between tough-nosed lawmen and some hard-headed outlaws in the town of Tombstone, near the Mexican border in the Arizona Territory.

But just to clarify: The shootout wasn’t even in a corral at all. It turns out, the shootout took place in a vacant lot, next to a photo studio and a boarding house.

Second point of clarification: Nobody ever called the standoff “the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” until Hollywood sunk its claws into the story in the late 1950s. The deadly scrap was well-known by historians, but to them it was just a fight. It wasn’t “the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” until 1957’s Burt Lancaster-Kirk Douglas blockbuster, “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.”

Which, you have to admit, does sound way cooler than “Gunfight in a Vacant Lot.”

“That doesn’t play well. But ‘Gunfight at the O.K. Corral’ is magic. It’s all in a name. Everything’s in the name,” says Marshall Trimble, Arizona’s official state historian. “I’ve written about 25 books and the hardest part of the whole thing is coming up with a catchy name.”

The Backstory of Tombstone

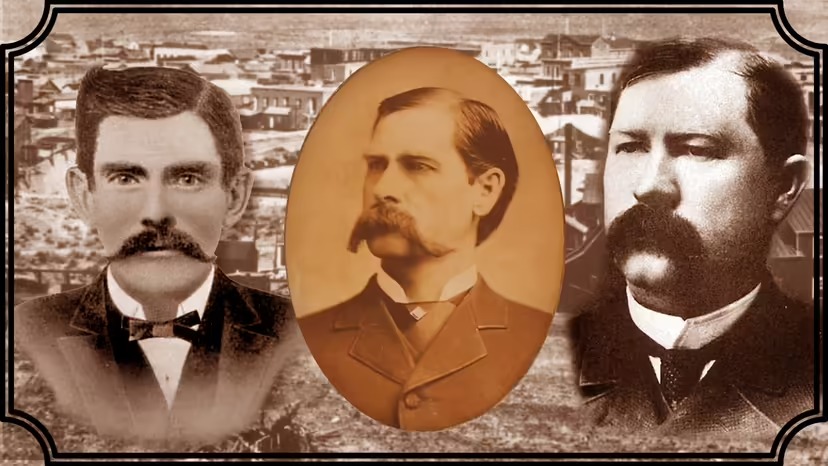

In true Western fashion, the cast of the real-life fight is easily broken into two groups.

The “Good Guys” were the lawmen in an otherwise lawless part of the Arizona Territory. They were Tombstone Marshal Virgil Earp, his brothers Morgan and Wyatt (both officially special policemen), and temporary policeman (and Wyatt Earp friend) John Henry “Doc” Holliday.

The “Bad Guys” were known as the “Cowboys,” a cow-rustling, horse-thieving group of no-good cusses who didn’t like the iron-handed Earps or anything to do with the law. They were Billy Claiborne, brothers Ike and Billy Clanton, and brothers Frank and Tom McLaury.

These two groups hated each other.

Long story short. Between 1879 and 1880, Tombstone’s population exploded with prospectors searching for silver ore and the town needed law enforcement. Town leaders wanted men like Virgil and Wyatt Earp because they had solid reputations as gunfighters and lawmen.

But the Clanton and McLaury families, who were prominent ranchers, formed their own coalition, known as the Cowboys, and they were against the Earp brothers and the law, even though the Earps had support from Tombstone’s leading businessmen, including Mayor John Clum and mining tycoon E.B. Gage.

Needless to say, the two groups had a history of run-ins. The Cowboys didn’t recognize Virgil Earp as marshal or his legal authority, and the Cowboys despised the fact that Earp and his “lawmen” often used possibly extra-legal methods to enforce the law.

The Gunfight of All Gunfights

In late 1881, it was against the law to carry weapons within the Tombstone town limits. Virgil Earp let that be known to the Cowboys. And that’s how things started that day.

After some threats and two pistol-whippings — the Earps didn’t take any guff from scofflaws, and both Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury tasted a little frontier justice from the handles of the Earps’ pistols earlier that day — the two groups squared off at about 3 p.m. Oct. 26. Most estimates put the two groups not much farther than 6 feet (1.8 meters) apart. There were plenty of guns present. Holliday carried a shotgun.

“When [the Cowboys] came into town and Billy [Clanton] saw his brother Ike had been hit, and Frank saw his brother Tom had been cocked, they were spoiling for a fight then,” Trimble says. “They made open threats that they were going to kill the Earps. They were overheard, and that’s what saved the Earps and Doc from maybe going to a murder trial.”

Here, we jump ahead to the firsthand witness account of John H. Behan. He was the sheriff of Cochise County, a political rival to the Earps and a friend to many of the Cowboys, and one of many interviewed afterward during a hearing into the gunfight. This courtesy of the Arizona Memory Project (typos part of the official transcript):

When they go;to the party of cowboys they drew their guns and sa said you sons of bitches you have been looking for a fight and you can have it. Someone of the party I think Marshall Earp said throw up your hands we are going to disarm you … Instantaniously with that the fight commenced the fought around there and their was and there was some 25 to 30 shots fired …

Over the years, dozens and dozens of accounts have been written on the fight, many relying on firsthand accounts like Behan’s (and others). Some say that at least one of the Cowboys was unarmed. Others refute that claim. Questions arose as to who fired the first shot, and who shot whom. But the toll of the gunfight is not in question.

Once everything had quieted down, three Cowboys — Billy Clanton, just 18 or 19 years old at the time, and both McLaury brothers — were dead.

The fight lasted no more than 30 seconds.

“That was kind of how it played out. In the end, Morgan Earp almost had a fatal wound. The bullet just missed his spine. But it went right clear through his back,” Trimble says. “Virgil took a hit in his leg. And Doc just got a scrape.

“Wyatt come through without a scratch. Just like he does in the movies.”

The Fallout From the Gunfight

Four days after the fight, Ike Clanton — who had fled once bullets started flying — accused the Earps and Holliday of murder, and Tombstone Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer held a hearing into the throwdown. Behan backed the Cowboys, but others supported the Earps and Holliday.

The verdict, Trimble says, may have hinged on the testimony of Addie Bourland, a local dressmaker, who contradicted the Cowboys who claimed that they had their hands up and should not have been fired upon. An excerpt from her testimony, via Famous Trials, by the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s Douglas O. Linder:

I didn’t see anyone holding up their hands; they all seemed to be firing in general, on both sides. They were firing on both sides, at each other; I mean by this at the time the firing commenced.

Despite the damning — and quite probably false — testimony from Ike Clanton and others, Spicer eventually found that the Earps and Holliday were well within their rights and declared that no trial was necessary.

Ike Clanton, bent on revenging the death of his brother and the other Cowboys, is generally thought to be behind the assassination attempt on Virgil Earp in December of that year and the murder of Morgan Earp, who was gunned down in a Tombstone billiard club in early 1882. After Morgan’s killing, Wyatt Earp tracked down some of Clanton’s cohorts, killing a couple. Clanton was killed by a detective in Springerville, Arizona Territory, in 1887 while resisting arrest.

Wyatt was the last of the O.K. Corral survivors. He died in Los Angeles in 1929, at age 80.

The Gunfight as Legend Today

The gunfight gained near mythic status in 1931, after Stuart Lake — a former press agent for president Theodore Roosevelt and a Hollywood writer — interviewed Wyatt and published a loose biography titled “Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal.” Then came the movie. A TV series on Wyatt Earp’s life and times (starring Hugh O’Brian) ran from 1955 to 1961.

Among the actors who have portrayed Earp (including Lancaster in the 1957 movie, opposite Douglas playing the part of Doc Holliday): Henry Fonda (“My Darling Clementine,” 1946), James Garner (“Hour of the Gun,” 1967), Kurt Russell (“Tombstone,” 1993), Kevin Costner (“Wyatt Earp,” 1994) and Val Kilmer (“Wyatt Earp’s Revenge,” 2012).

Clanton’s testimony in the Spicer hearings was the basis of several latter-day recountings of the fight that threw Wyatt Earp’s reputation into question.

“I think it’s the psychology that people like to believe that a good guy can’t be that good. And Wyatt wasn’t,” Trimble says. “Wyatt had a little shady past — all of them did.

“I tell people, these were sporting men. Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson … these guys were sporting men. They ran around with prostitutes, gambled, hung out with an unsavory lot. But Wyatt came from good stock. He came from a good family. Wyatt was a whole lot better than the others. He was just a product of his time.”

Tourists now stream into Tombstone to see reenactments — four times a day, except on Thanksgiving and Christmas — of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Beyond Tombstone that face-to-face showdown between a lawless bunch of cowboys and a hardened bunch of lawmen has given Arizona and the entire West a huge part of its identity. Larger even than that, for many visitors, the gunfight is a snapshot of America.

“A lot of Arizonans just roll their eyes when they see these reenactments. But I never complain. And I’ve seen hundreds of them,” Trimble says. “The tourists just love it. They come over here and they want to come to Tombstone, because you can’t come to America without coming to Tombstone.

“Gunfighters are America’s rendition of King Arthur’s Knights of the Roundtable. They are the warriors. People are fascinated by them, because they had a code of their own. And it’s an independence — a free-spirited independence. It’s what everybody wishes they could be but aren’t.”

By John Donovan